Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield

November 18, 2002, Greencastle, Ind. - "What we started to learn at Ben & Jerry's is that there's a spiritual aspect to business, just as there is to the lives of individuals," Ben Cohen told a crowd of about 1,000 inside 69É«ÇéĘÓƵ's Kresge Auditorium, where tonight he and his former business partner, Jerry Greenfield, presented a Timothy and Sharon Ubben Lecture. "As you give, you receive. As you help others, you're helped in return. For people, for business, for nations, it's all the same," Cohen added. The two men, known for their tasty ice cream and people-first business practices presented "An Evening of Entrepreneurial Spirit, Social Responsibility and Radical Business Philosophy." (photo shows Ben & Jerry posing for pictures with DePauw students after their Ubben Lecture)

November 18, 2002, Greencastle, Ind. - "What we started to learn at Ben & Jerry's is that there's a spiritual aspect to business, just as there is to the lives of individuals," Ben Cohen told a crowd of about 1,000 inside 69É«ÇéĘÓƵ's Kresge Auditorium, where tonight he and his former business partner, Jerry Greenfield, presented a Timothy and Sharon Ubben Lecture. "As you give, you receive. As you help others, you're helped in return. For people, for business, for nations, it's all the same," Cohen added. The two men, known for their tasty ice cream and people-first business practices presented "An Evening of Entrepreneurial Spirit, Social Responsibility and Radical Business Philosophy." (photo shows Ben & Jerry posing for pictures with DePauw students after their Ubben Lecture)

The offbeat entrepreneurs were greeted with thunderous applause as they took Kresge's stage with Gary Lemon, professor of economics and director of DePauw's Management Fellows Program and the Robert C. McDermond Center for Management and Entrepreneurship, who emceed the proceedings. Saying that he and Cohen were "very excited " to be at DePauw and "very happy to see our holstein headbands up front and a lot of Ben & Jerry's support," Jerry Greenfield began the program by describing the humble beginnings of a product that is now a household name.

The offbeat entrepreneurs were greeted with thunderous applause as they took Kresge's stage with Gary Lemon, professor of economics and director of DePauw's Management Fellows Program and the Robert C. McDermond Center for Management and Entrepreneurship, who emceed the proceedings. Saying that he and Cohen were "very excited " to be at DePauw and "very happy to see our holstein headbands up front and a lot of Ben & Jerry's support," Jerry Greenfield began the program by describing the humble beginnings of a product that is now a household name.

Ben & Jerry became friends in high school and went their separate ways for awhile, but decided to go into business after failed attempts at becoming a potter (Ben) and entering medical school (Jerry). "We thought, boy, why don't we try to get together, do something that's fun, be our own bosses? Since we always liked to eat quite a bit, we thought we'd do something with food: we picked ice cream, didn't know anything about it. As Gary said [in his introduction], we took a $5 correspondence course from Penn State. What he didn't say is we were really broke at the time, and so we split one course between us," Greenfield said to laughter from the crowd.

Jerry detailed the events that led to the two men opening an ice cream parlor in the college town of Burlington, Vermont in 1978 (seen at right), and how they dealt with challenges, including how to keep business thriving during the cold winter months-- they started packing their ice cream for sale to local restaurants and eventually convinced locally-owned grocery stores to stock the creamy confection. "Ben would stop at these stores, introduce himself, 'hi, I'm Ben from Ben & Jerry's.' They'd say 'hi,' he'd say 'Would you like to buy some of our ice cream?' and they'd say, 'No, not really' because it was the middle of winter in Vermont, it was -20 degrees out. And so Ben thought, if it doesn't sell, we'll buy it back from you... And these are smart Vermonters and they know a good deal when they could hear one. Ben got us about 50 accounts our first month and a couple hundred after that, and that is how we stumbled into the manufacturing and distribution business."

Jerry detailed the events that led to the two men opening an ice cream parlor in the college town of Burlington, Vermont in 1978 (seen at right), and how they dealt with challenges, including how to keep business thriving during the cold winter months-- they started packing their ice cream for sale to local restaurants and eventually convinced locally-owned grocery stores to stock the creamy confection. "Ben would stop at these stores, introduce himself, 'hi, I'm Ben from Ben & Jerry's.' They'd say 'hi,' he'd say 'Would you like to buy some of our ice cream?' and they'd say, 'No, not really' because it was the middle of winter in Vermont, it was -20 degrees out. And so Ben thought, if it doesn't sell, we'll buy it back from you... And these are smart Vermonters and they know a good deal when they could hear one. Ben got us about 50 accounts our first month and a couple hundred after that, and that is how we stumbled into the manufacturing and distribution business."

Before long, Ben & Jerry's ice cream was being shipped outside of Vermont, and became known nationally for its rich, unusual flavors, all-natural ingredients (Ben & Jerry's is committed to using milk and cream that have not been treated with the synthetic hormone, rBGH) and community approach to business. But the company was, in Ben Cohen's words, "bursting at the seams," and needed an infusion of cash to grow, thrive and survive. He and his partner were approached by a number of venture capitalists: investors with big money who wanted to put it behind Ben & Jerry's. Instead, the men decided to sell modestly-priced shares to the people of Vermont, "to make the community the owners of the business. So that, as the business grew, the community would automatically prosper."

Before long, Ben & Jerry's ice cream was being shipped outside of Vermont, and became known nationally for its rich, unusual flavors, all-natural ingredients (Ben & Jerry's is committed to using milk and cream that have not been treated with the synthetic hormone, rBGH) and community approach to business. But the company was, in Ben Cohen's words, "bursting at the seams," and needed an infusion of cash to grow, thrive and survive. He and his partner were approached by a number of venture capitalists: investors with big money who wanted to put it behind Ben & Jerry's. Instead, the men decided to sell modestly-priced shares to the people of Vermont, "to make the community the owners of the business. So that, as the business grew, the community would automatically prosper."

Eventually, as the company continued to grow, it sold shares on a national level, and locked in policies that ensured that the community would benefit from Ben & Jerry's ascent. The two founders earmarked 7.5% of all pre-tax profits for donation to not-for-profit organizations which facilitate progressive social change by addressing the underlying conditions of societal and environmental problems, and gave the job of determining how that money is distributed to a team of Ben & Jerry's employees. The Council on Economic Priorities honored Ben & Jerry with the 1988 Corporate Giving Award. That same year, the men were named America's Small Business Persons of the Year by the US Small Business Administration, were recognized as the James Beard Humanitarians of the Year award in 1993 and as the Peace Museum's Community Peacemakers of the Year award in 1997.

Ben & Jerry, who began their day on the DePauw campus by visiting student radio station WGRE, being interviewed by The DePauw (which was videotaped by D3TV, the student television operation), and dining with DePauw students (see accompanying photos), no longer control the company they founded. In 2000, the board of Ben & Jerry's sold the firm to a major conglomerate, Unilever. "They have a really good sense of humor," Jerry says of the ice cream-maker's new owner. "On the same day they bought Ben & Jerry's, they also bought SlimFast (laughter). Selling the company is not something that we wanted to have happen... but we were a public company at the time, and they offered so much money [to shareholders] it got sold."

Ben & Jerry, who began their day on the DePauw campus by visiting student radio station WGRE, being interviewed by The DePauw (which was videotaped by D3TV, the student television operation), and dining with DePauw students (see accompanying photos), no longer control the company they founded. In 2000, the board of Ben & Jerry's sold the firm to a major conglomerate, Unilever. "They have a really good sense of humor," Jerry says of the ice cream-maker's new owner. "On the same day they bought Ben & Jerry's, they also bought SlimFast (laughter). Selling the company is not something that we wanted to have happen... but we were a public company at the time, and they offered so much money [to shareholders] it got sold."

Jerry Greenfield remains with the company as vice-chair of the board and director of mobile promotions and continues to oversee the work of the Ben & Jerry's Foundation. Ben Cohen also remains a force for positive change. His main project is TrueMajority, an enterprise aimed at reducing world poverty and hunger, promoting renewable energy and closing the gap between the rich and poor in the United States by making people more aware of the issues of the day (learn more by ).

Cohen says religion was once the most powerful source in society, then it was government. Within his lifetime, Cohen says, business has become the top force. "As that most powerful force, business controls our society. It controls our media through ownership. It controls our elections through campaign contributions. It controls our legislation through lobbyists. And it controls our everyday lives as employees and customers. And yet, all of that is done in the narrow self-interest of business without a concern for the welfare of society as a whole."

Cohen says religion was once the most powerful source in society, then it was government. Within his lifetime, Cohen says, business has become the top force. "As that most powerful force, business controls our society. It controls our media through ownership. It controls our elections through campaign contributions. It controls our legislation through lobbyists. And it controls our everyday lives as employees and customers. And yet, all of that is done in the narrow self-interest of business without a concern for the welfare of society as a whole."

Ben Cohen says that mindset must change if the world is to defeat its ills, including poverty, famine, the decline of the environment and the defeat of repression. And, he says, government must re-think its priorities and reduce military spending, where he maintains America behaves as if the Cold War is still at its peak. "I was there in the shower the other day-- I'm adjusting things, I've got good temperature, I've got good pressure, I'm lathering up, things are going well, I'm shampooing, I'm rinsing down-- and I open up the shower door, look in the mirror and realize that I've been spending 90% of my shampoo time on the top of my head, and it's not needed there anymore," the follically-challenged Cohen said to laughter from his audience. "This is institutional lag. I just had that little case of it. Imagine what a big case the government has."

Ben Cohen says that mindset must change if the world is to defeat its ills, including poverty, famine, the decline of the environment and the defeat of repression. And, he says, government must re-think its priorities and reduce military spending, where he maintains America behaves as if the Cold War is still at its peak. "I was there in the shower the other day-- I'm adjusting things, I've got good temperature, I've got good pressure, I'm lathering up, things are going well, I'm shampooing, I'm rinsing down-- and I open up the shower door, look in the mirror and realize that I've been spending 90% of my shampoo time on the top of my head, and it's not needed there anymore," the follically-challenged Cohen said to laughter from his audience. "This is institutional lag. I just had that little case of it. Imagine what a big case the government has."

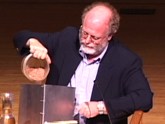

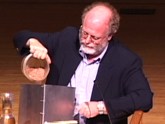

Using a jar of BB's and a metal container, Cohen demonstrated how large the USA's nuclear stockpile is (see and hear it: ). "That was 10,000 BB's, the equivalent of 150,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs," enough to blow up the world 10 times over, yet Cohen says former military leaders he's talked with believe America needs only enough weaponry to blow up the world four times over. Eliminating the difference "would save us $15 billion a year, and that's enough money to rebuild all of our schools and provide health care for all those kids who don't have any today."

Using a jar of BB's and a metal container, Cohen demonstrated how large the USA's nuclear stockpile is (see and hear it: ). "That was 10,000 BB's, the equivalent of 150,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs," enough to blow up the world 10 times over, yet Cohen says former military leaders he's talked with believe America needs only enough weaponry to blow up the world four times over. Eliminating the difference "would save us $15 billion a year, and that's enough money to rebuild all of our schools and provide health care for all those kids who don't have any today."

Before sending his DePauw audience back to the lobby, where all were treated to a free helping of Ben & Jerry's ice cream, Cohen said, "Our country, the last remaining superpower on Earth, needs to learn to measure its strength not in terms of how many people we can kill, but in terms of how many people we can feed, clothe, house and care for."

November 18, 2002, Greencastle, Ind. - "What we started to learn at Ben & Jerry's is that there's a spiritual aspect to business, just as there is to the lives of individuals," Ben Cohen told a crowd of about 1,000 inside 69É«ÇéĘÓƵ's Kresge Auditorium, where tonight he and his former business partner, Jerry Greenfield, presented a Timothy and Sharon Ubben Lecture. "As you give, you receive. As you help others, you're helped in return. For people, for business, for nations, it's all the same," Cohen added. The two men, known for their tasty ice cream and people-first business practices presented "An Evening of Entrepreneurial Spirit, Social Responsibility and Radical Business Philosophy." (photo shows Ben & Jerry posing for pictures with DePauw students after their Ubben Lecture)

November 18, 2002, Greencastle, Ind. - "What we started to learn at Ben & Jerry's is that there's a spiritual aspect to business, just as there is to the lives of individuals," Ben Cohen told a crowd of about 1,000 inside 69É«ÇéĘÓƵ's Kresge Auditorium, where tonight he and his former business partner, Jerry Greenfield, presented a Timothy and Sharon Ubben Lecture. "As you give, you receive. As you help others, you're helped in return. For people, for business, for nations, it's all the same," Cohen added. The two men, known for their tasty ice cream and people-first business practices presented "An Evening of Entrepreneurial Spirit, Social Responsibility and Radical Business Philosophy." (photo shows Ben & Jerry posing for pictures with DePauw students after their Ubben Lecture) The offbeat entrepreneurs were greeted with thunderous applause as they took Kresge's stage with Gary Lemon, professor of economics and director of DePauw's Management Fellows Program and the Robert C. McDermond Center for Management and Entrepreneurship, who emceed the proceedings. Saying that he and Cohen were "very excited " to be at DePauw and "very happy to see our holstein headbands up front and a lot of Ben & Jerry's support," Jerry Greenfield began the program by describing the humble beginnings of a product that is now a household name.

The offbeat entrepreneurs were greeted with thunderous applause as they took Kresge's stage with Gary Lemon, professor of economics and director of DePauw's Management Fellows Program and the Robert C. McDermond Center for Management and Entrepreneurship, who emceed the proceedings. Saying that he and Cohen were "very excited " to be at DePauw and "very happy to see our holstein headbands up front and a lot of Ben & Jerry's support," Jerry Greenfield began the program by describing the humble beginnings of a product that is now a household name. Jerry detailed the events that led to the two men opening an ice cream parlor in the college town of Burlington, Vermont in 1978 (seen at right), and how they dealt with challenges, including how to keep business thriving during the cold winter months-- they started packing their ice cream for sale to local restaurants and eventually convinced locally-owned grocery stores to stock the creamy confection. "Ben would stop at these stores, introduce himself, 'hi, I'm Ben from Ben & Jerry's.' They'd say 'hi,' he'd say 'Would you like to buy some of our ice cream?' and they'd say, 'No, not really' because it was the middle of winter in Vermont, it was -20 degrees out. And so Ben thought, if it doesn't sell, we'll buy it back from you... And these are smart Vermonters and they know a good deal when they could hear one. Ben got us about 50 accounts our first month and a couple hundred after that, and that is how we stumbled into the manufacturing and distribution business."

Jerry detailed the events that led to the two men opening an ice cream parlor in the college town of Burlington, Vermont in 1978 (seen at right), and how they dealt with challenges, including how to keep business thriving during the cold winter months-- they started packing their ice cream for sale to local restaurants and eventually convinced locally-owned grocery stores to stock the creamy confection. "Ben would stop at these stores, introduce himself, 'hi, I'm Ben from Ben & Jerry's.' They'd say 'hi,' he'd say 'Would you like to buy some of our ice cream?' and they'd say, 'No, not really' because it was the middle of winter in Vermont, it was -20 degrees out. And so Ben thought, if it doesn't sell, we'll buy it back from you... And these are smart Vermonters and they know a good deal when they could hear one. Ben got us about 50 accounts our first month and a couple hundred after that, and that is how we stumbled into the manufacturing and distribution business." Before long, Ben & Jerry's ice cream was being shipped outside of Vermont, and became known nationally for its rich, unusual flavors, all-natural ingredients (Ben & Jerry's is committed to using milk and cream that have not been treated with the synthetic hormone, rBGH) and community approach to business. But the company was, in Ben Cohen's words, "bursting at the seams," and needed an infusion of cash to grow, thrive and survive. He and his partner were approached by a number of venture capitalists: investors with big money who wanted to put it behind Ben & Jerry's. Instead, the men decided to sell modestly-priced shares to the people of Vermont, "to make the community the owners of the business. So that, as the business grew, the community would automatically prosper."

Before long, Ben & Jerry's ice cream was being shipped outside of Vermont, and became known nationally for its rich, unusual flavors, all-natural ingredients (Ben & Jerry's is committed to using milk and cream that have not been treated with the synthetic hormone, rBGH) and community approach to business. But the company was, in Ben Cohen's words, "bursting at the seams," and needed an infusion of cash to grow, thrive and survive. He and his partner were approached by a number of venture capitalists: investors with big money who wanted to put it behind Ben & Jerry's. Instead, the men decided to sell modestly-priced shares to the people of Vermont, "to make the community the owners of the business. So that, as the business grew, the community would automatically prosper." Ben & Jerry, who began their day on the DePauw campus by visiting student radio station WGRE, being interviewed by The DePauw (which was videotaped by D3TV, the student television operation), and dining with DePauw students (see accompanying photos), no longer control the company they founded. In 2000, the board of Ben & Jerry's sold the firm to a major conglomerate, Unilever. "They have a really good sense of humor," Jerry says of the ice cream-maker's new owner. "On the same day they bought Ben & Jerry's, they also bought SlimFast (laughter). Selling the company is not something that we wanted to have happen... but we were a public company at the time, and they offered so much money [to shareholders] it got sold."

Ben & Jerry, who began their day on the DePauw campus by visiting student radio station WGRE, being interviewed by The DePauw (which was videotaped by D3TV, the student television operation), and dining with DePauw students (see accompanying photos), no longer control the company they founded. In 2000, the board of Ben & Jerry's sold the firm to a major conglomerate, Unilever. "They have a really good sense of humor," Jerry says of the ice cream-maker's new owner. "On the same day they bought Ben & Jerry's, they also bought SlimFast (laughter). Selling the company is not something that we wanted to have happen... but we were a public company at the time, and they offered so much money [to shareholders] it got sold." Cohen says religion was once the most powerful source in society, then it was government. Within his lifetime, Cohen says, business has become the top force. "As that most powerful force, business controls our society. It controls our media through ownership. It controls our elections through campaign contributions. It controls our legislation through lobbyists. And it controls our everyday lives as employees and customers. And yet, all of that is done in the narrow self-interest of business without a concern for the welfare of society as a whole."

Cohen says religion was once the most powerful source in society, then it was government. Within his lifetime, Cohen says, business has become the top force. "As that most powerful force, business controls our society. It controls our media through ownership. It controls our elections through campaign contributions. It controls our legislation through lobbyists. And it controls our everyday lives as employees and customers. And yet, all of that is done in the narrow self-interest of business without a concern for the welfare of society as a whole." Ben Cohen says that mindset must change if the world is to defeat its ills, including poverty, famine, the decline of the environment and the defeat of repression. And, he says, government must re-think its priorities and reduce military spending, where he maintains America behaves as if the Cold War is still at its peak. "I was there in the shower the other day-- I'm adjusting things, I've got good temperature, I've got good pressure, I'm lathering up, things are going well, I'm shampooing, I'm rinsing down-- and I open up the shower door, look in the mirror and realize that I've been spending 90% of my shampoo time on the top of my head, and it's not needed there anymore," the follically-challenged Cohen said to laughter from his audience. "This is institutional lag. I just had that little case of it. Imagine what a big case the government has."

Ben Cohen says that mindset must change if the world is to defeat its ills, including poverty, famine, the decline of the environment and the defeat of repression. And, he says, government must re-think its priorities and reduce military spending, where he maintains America behaves as if the Cold War is still at its peak. "I was there in the shower the other day-- I'm adjusting things, I've got good temperature, I've got good pressure, I'm lathering up, things are going well, I'm shampooing, I'm rinsing down-- and I open up the shower door, look in the mirror and realize that I've been spending 90% of my shampoo time on the top of my head, and it's not needed there anymore," the follically-challenged Cohen said to laughter from his audience. "This is institutional lag. I just had that little case of it. Imagine what a big case the government has." Using a jar of BB's and a metal container, Cohen demonstrated how large the USA's nuclear stockpile is (see and hear it: ). "That was 10,000 BB's, the equivalent of 150,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs," enough to blow up the world 10 times over, yet Cohen says former military leaders he's talked with believe America needs only enough weaponry to blow up the world four times over. Eliminating the difference "would save us $15 billion a year, and that's enough money to rebuild all of our schools and provide health care for all those kids who don't have any today."

Using a jar of BB's and a metal container, Cohen demonstrated how large the USA's nuclear stockpile is (see and hear it: ). "That was 10,000 BB's, the equivalent of 150,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs," enough to blow up the world 10 times over, yet Cohen says former military leaders he's talked with believe America needs only enough weaponry to blow up the world four times over. Eliminating the difference "would save us $15 billion a year, and that's enough money to rebuild all of our schools and provide health care for all those kids who don't have any today."